Part 2: Blockchain Present and Beyond

This is a continuation from Part 1: Blockchain Origin Story

Now let’s talk about the state of blockchain technologies now, circa 2017. How has it changed since it was first used in 2009?

Evolution of Bitcoin

Since Bitcoin was launched in early 2009 it has grown immensely. It is now disrupting financial markets and inspiring startups to follow suit and leap into blockchain technologies.

While there have been major changes to Bitcoin since it was launched, its blockchain remains the same unbroken link of transactions from the genesis block. That chain is now more than 100GB and it’s still growing - even faster as the popularity of Bitcoin increases. This overhead will have to be addressed in the near future.

Since the Bitcoin source code is open, it’s possible to fork the code base and change it to create an ‘altcoin’. In fact, many have done this and have varying levels of support and valuation. The valuation of cryptocurrency is an interesting study and certainly keeps a lot of people busy guessing - and has made some of them very wealthy.

Ethereum

Image Credit: Ethereum Group

Image Credit: Ethereum Group

For some time blockchains were primarily proof of work cryptocurrencies. One of the first steps of a blockchain moving beyond this was Ethereum in 2015, when Ethereum launched a platform that supported, in addition to cryptocurrency, smart contracts.

Smart Contracts

Smart contracts take traditional contracts and make them a part of a distributed ledger. First, let’s consider a traditional, legally binding contract. It’s useful to review the definition of a contract, which per Webster, is:

An agreement or covenant between two or more persons, in which each party binds himself to do or forbear some act, and each acquires a right to what the other promises

The enforcement of a contract is typically done through the law. Let’s say Alice would like to contract with Eve to perform yard work. The terms of the contract are that Alice weeds 100 dandelions. Upon completion of that task, Eve is contracted to pay Alice $20. The contract further stipulates that Alice may weed additional dandelions and be paid $0.10 each. Finally, Eve’s neighbor Bob is named as a mediator to validate the number of dandelions picked if a dispute arises.

Alice begins pulling dandelions from Eve’s yard and eventually finishes, having pulled 150 dandelions. Per the contract Alice is due $25, however Eve decides to pay her only $10. At this point the contract has been broken and Alice may bring in Bob as mediator and possibly pursue legal action against Eve.

| Party | Role |

|---|---|

| Alice | Pick dandelions |

| Eve | Pay agreed rate of $0.20 per dandelion up to 100, $0.10 thereafter |

| Bob | Arbitrate payment in the event of a dispute |

Table 1 - Contract Example

Smart contracts are protocols that allow a contract to be computerized in a way that they are automatically facilitated, verified, and enforced. Consider the example above as a smart contract. The terms are the same, but instead of being paid $20 for 100 and $0.10 each thereafter, Eve promises to pay 100 ETH and .1 ETH each thereafter, ETH being the cryptocurrency of the Ethereum blockchain.

These conditions are written as part of the smart contract and included in the blockchain, signed by all parties involved, signifying their agreement to the terms. Once both Alice and Eve agree on the number of dandelions picked, the smart contract would automatically execute and Alice would be given her 25 ETH. Bob may still play a role as a third party, he simply needs to be written into the smart contract. Furthermore, smart contracts allow this sort of interaction between anonymous and untrusted parties and works particularly well for transfer of on-chain assets (typically cryptocurrency, specifically Ethereum in this case).

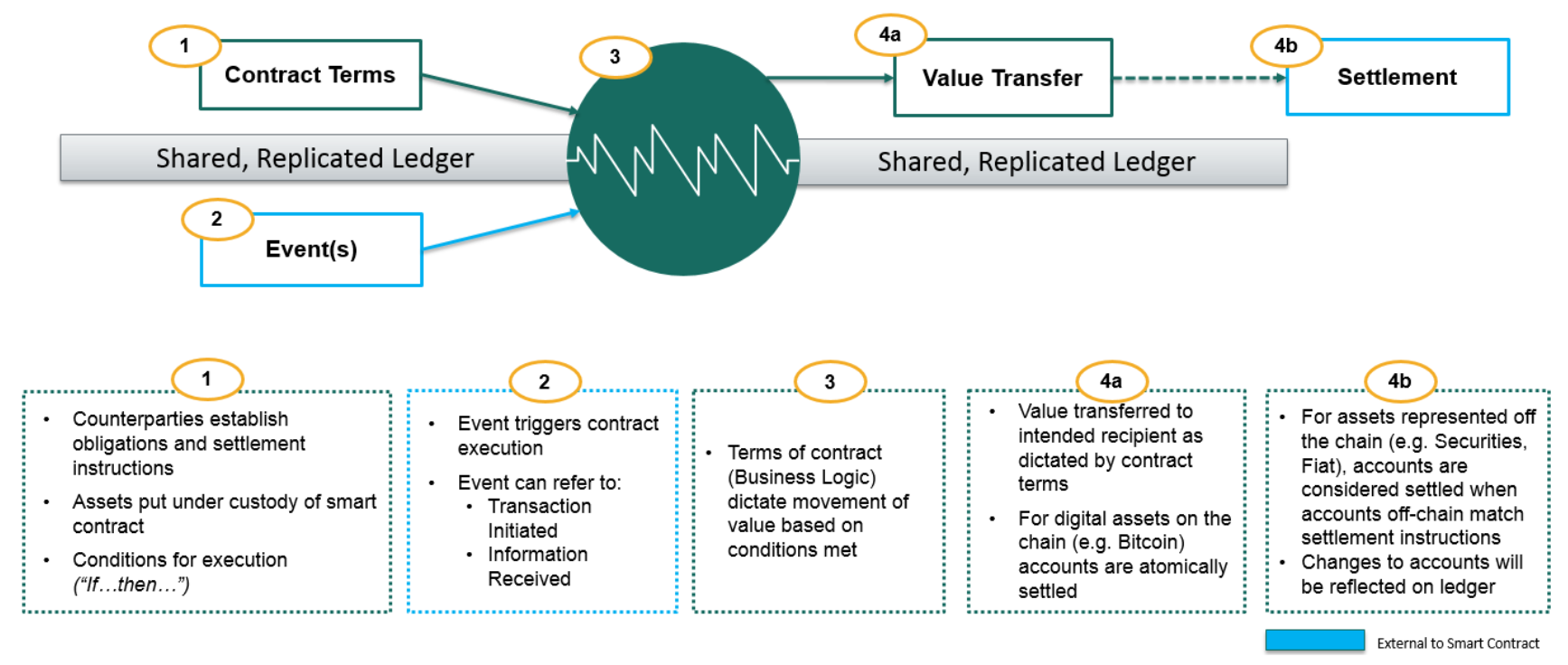

A good definition for smart contracts was given by Richard Brown:

A smart-contract is an event-driven program, with state, which runs on a replicated, shared ledger and which can take custody over assets on that ledger.

Figure 1 below generalizes well how a smart contract might live on a blockchain (which the figure labels a “shared, replicated ledger”).

Figure 1 - Smart Contract; Image credit: Jo Lang / R3 CEV

Figure 1 - Smart Contract; Image credit: Jo Lang / R3 CEV

There is incredible potential in smart contracts which we will discuss later. However, some of the proposed use cases for smart contracts have been shown to be infeasible. Smart contracts have limitations, and it’s important to understand what place they might have in future blockchain technology, or your own organization.

Beyond Smart Contracts

The Ethereum Project made an interesting decision to further expand smart contracts - Turing completeness. If something is Turing complete, it can calculate pi, send an email, and play Doom (although the framerate will make it unplayable since very slow, computing 25 transactions per second (as of January 2016))

This is what Ethereum calls the Ethereum World Computer or the Ethereum Virtual Machine. It sounds a bit like Deep Thought from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, but it is hopefully a bit faster at coming up with the answer 42.

Figure 2 - Deep Thought; Image credit: Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Figure 2 - Deep Thought; Image credit: Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

It’s important to remember that Smart contracts are computer code. Computer code may have flaws, and arbitrary code will have arbitrary flaws. It’s only a matter of time until smart contracts are executed erroneously using a vulnerability in the smart contract code.

One more thing - smart contracts are computer code, and computer code may contain bugs. Consider what can go wrong with buggy code and an immutable blockchain; anyone embracing smart contracts should be fully aware of the risks.

Proof of Stake

Proof of Stake (PoS) algorithms are an alternative to proof of work mechanism used to achieve distributed consensus among peers. Instead of competing to generate an acceptable hash using intense computational power, PoS determines the next block winner in a deterministic way based on the stake of the account holder.

There are different implementations that use different methods to choose the next block owner, such as randomization or ‘coin age’ (the time since that coin has been awarded a block). In either case, the probability increases with the amount of stake the account holder has. If you own more coins, the likelihood that you will be awarded a block is increased.

This area of development is very interesting because it answers, in part, a very significant drawback of the proof of work consensus system - the wasted energy and work expended in keeping the blockchain secure. For example, in 2014 the energy consumption to mint a bitcoin was equivalent to 16 gallons of gasoline. The costs have only increased. Ethereum has announced they plan to move to proof of stake for block generation in the future and many new cryptocurrencies are opting to use proof of stake instead.

Beyond Blockchain: Permissioned Ledgers

Bitcoin and Ethereum are considered permissionless systems - in other words, their users are largely anonymous or at least pseudonymous. They do not require permission to become a part of either network. There are no gatekeepers. The transactions may be verified by the public, and transactions may be initialized by the public (as long as they have bitcoins or ether to spend).

Conversely, a permissioned system has some sort of authentication to ensure that only permissioned users participate in the ledger. Permissioned ledgers may still be validated by the public but may only be written to by trusted (permissioned) individuals. Or, they may be completely private - accessing and contributing to the ledger restricted to authenticated nodes only.

Permissionless (Public):

- Publicly readable (& verifiable)

- Publicly writable

Permissioned (Private):

- Publicly or privately readable

- Privately writable

Permissioned ledgers greatly expand the potential applications of blockchain technology. For example, banks are not interested in a cryptocurrency that relies on anonymous validation (such as Bitcoin or Ethereum), especially when banks don’t benefit from the anonymity that comes at such a high cost - banks send or receive money from other legitimate banks. Instead of using permissionless cryptocurrencies, the bank may fork Bitcoin into an altcoin that only allow transactions signed by known good actors (that they can authenticate).

All the organizations that are uncomfortable with using a distributed ledger subject to an anonymous majority now have the opportunity to exploit the advantages of blockchains without sacrificing control or paying the overhead of proof of work.

Others

Beyond the myriad alternative altcoins that have multiplied in the years since Bitcoin, there are some noteworthy applications of blockchains that are worthy of a quick overview.

ICO

A phenomenon that has become more common and newsworthy in recent months is the Initial Coin Offering (ICO). Meant to mimic an Initial Public Offering (IPO), ICOs offer a limited block of cryptocurrency for sale to the public. This is meant to generate an influx of cash into the company and, like an IPO, is a risky venture.

ICOs don’t represent anything new in blockchain technology, but are instead new ways of distributing the cryptocurrency. They are likely here to stay, but may be regulated in the future.

Blockchain Future

Off-Ledger Integration

Since much of the blockchain development has been around permissionless (and anonymous) blockchains, the idea of involving off-chain assets (property, goods, services) has not been seriously attempted until fairly recently. One of the problems facing integrating off-chain assets is legal enforceability of blockchain contracts. If a permissioned ledger uses legally accountable validators (known as miners in Bitcoin) and meets other legal criteria, it could pass government regulatory requirements.

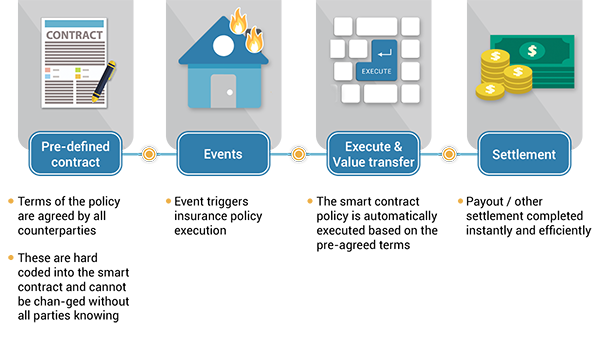

Insurance

A particularly good application for smart contracts is the Insurance industry. Figure 3 shows how an insurance claim that is executed by smart contract could work.

Figure 3 - Smart Contract Example for Insurance; Image Credit: Wikipedia

Figure 3 - Smart Contract Example for Insurance; Image Credit: Wikipedia

Real Estate

Extending smart contracts to real estate has potential to bypass an entire cottage industry dedicated to taking a large cut from the homebuying process at the expense of the home buyers and, to a greater extent, the sellers. Buying a home is an expensive and risky process, but if you could automate much of the contracts through a distributed ledger with smart contracts that appropriately (and legally) incorporated off-ledger assets (such as titles), the cost and time required to buy a house could be significantly decreased.

Government

Government bureaucracy costs us billions annually. Incorporating distributed ledgers with trusted verifiers maintained by the government would save the American taxpayer a significant amount of money by ensuring automatic regulatory compliance. Furthermore, the various state governments could each maintain their own authorized permissioned ledgers that interoperate with other ledgers, such as those envisioned by Hyperledger below. Much of government records are public record - maintaining them in the public eye in a verifiable manner would bring our government into the digital age in a manner never conceived.

Private ledgers promise to provide the same benefits for data that isn’t public, but still needs a verifiable chain of custody. The original vision for blockchains was to timestamp edits to a digital document. Private ledgers could provide similar chains of custody for classified documents that would help avoid a Snowden-like scenario in the future.

Chain of Custody

Consider the following scenario: You are a hardware manufacturer that developes and produces high-end hardware. You are successful, however you notice that counterfeit versions of your hardware is beginning to enter the market. Any attempt you make to change your hardware to detect counterfeits are easily incorporated by the counterfeiters. This story is very common with hardware producers, and they all fight counterfeits with varying levels of success.

What if our manufacturer in the story used a permissioned ledger? Every piece of hardware is included in a (block)chain of custody. The manufacturer signs each piece of hardware as they roll of the assembly line, possibly even using a form of RF-DNA (Radio Frequency DNA) to uniquely identify the emissions of computer hardware.

The wholesaler who purchases the products adds his signature to the chain of custody for each item, indicating that they are now in possession of each piece of hardware. The retailer who purchases the products from the wholesaler does the same thing, and the blockchain shows an uninterrupted chain of custody from the manufacturer to the retailer. When the hardware is purchased, the retailer can record the transaction and the chain of custody can reflect that the item has been purchased.

The consumer, or anyone at any time in this chain, can look up the unique serial number of the hardware and view the unbroken chain of custody back to the manufacturer. Furthermore, if the serial number is derived from the RF-DNA of the hardware, it would be difficult if not impossible to counterfeit.

This chain of custody example can extend to other assets as well, such as digital and high-value assets. Chain of custody is an application of blockchain technology that is most true to the 1991 paper by Haber and Stornetta than any I’ve covered in these articles.

Hyperledger

Image credit: The Linux Foundation

Image credit: The Linux Foundation

Started by the Linux foundation in 2015, Hyperledger is a collection of open source blockchains and tools. It is made up of different fledgling platforms that are sponsored by different organizations, including Intel and IBM.

Their vision includes enabling different parties to securely interact with the same universal source of truth, including:

Financial Institutions

Healthcare Organizations

Transportation Organizations

Their vision is that any industry could benefit from the immutability and public verifiability that blockchain offers.

Sovrin (Hyperledger Indy)

One of the more ambitions Hyperledger frameworks is Hyperledger Indy sponsored by the Sovrin Foundation. Sovrin aims to utilize blockchain technology to provide each human being a sovereign, digital identity. The foundation aims to provide identities that are “100% owned and controlled by an individual or organization” that can interoperate with other distributed ledgers.

Sovrin relies on a Public Permissioned ledger that allows anyone to manage their own identity, but only trusted distributed nodes can write to the ledger, and only when appropriate consensus is reached. Each identity holder (the public) can manager their individual identities, including who can see what attributes of their identity. It has potential to give voice and identity to the millions of refugees who don’t have either.

Of course the future is unknown and I’m no prophet. These are emergent applications of the technology and I’m sure some visionaries will find applications of distributed ledgers that no one can anticipate. That’s the beautify of this technology - we have some great minds focused on exploiting its potential.

Now, let’s see a little about the Privledge project, a blockchain proof of concept written in Python:

Continue to Part 3: Privledge